By Cheryl Sullenger

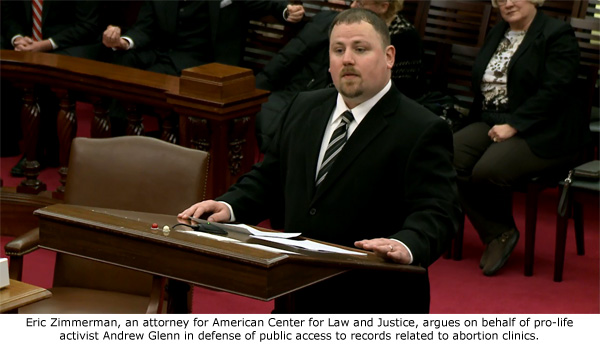

Annapolis, MD — An important case involving the non-disclosure of public records related to abortion clinics was heard by the Maryland Supreme Court, which engaged in lively questioning of both the attorney representing a pro-life activist who had requested public records and an attorney representing the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DHMH).

The attorney representing the DHMH argued that releasing the names of abortion clinic owners and administrators would post a risk of abortion clinic violence, and therefore should not be disclosed. He also claimed – without evidence to back it up — that the release would cause a chilling effect, discouraging some providers from doing abortions abortions.

However he admitted he was unaware that the Department of Health posts on its website clinic deficiency reports that already contain the names of clinic administrators.

There has been no recorded violence against abortion clinics or providers in Maryland.

“The only evidence of death or injury in Maryland is unfortunately against women who have sought services at abortion clinics,” Erik Zimmerman stated, who was representing pro-life activist Andrew Glenn.

In March 2013, inspectors discovered that a patient, Maria Santiago, died during an abortion at Brigham’s Baltimore abortion facility, which is located in a residential condominium complex. [Read the CAD and Police Report]

That same year, Jennifer Morbelli died from complications to a 33-week abortion she received from Nebraska abortionist LeRoy Carhart, who conducts abortions throughout all nine months of pregnancy at a clinic in Germantown, Maryland. Evidence exists that Carhart has sent numerous patients to hospital emergency rooms since he moved his late-term abortion business to Maryland five years ago.

Evidence of these tragedies and more have been obtained through public records requests made by pro-life activists.

The State had a difficult time answering questions from some of the justices, who asked how, for example, a woman seeking an abortion could check on the disciplinary history of an owner, administrator, or provider if the names of these people are kept from the public.

In addition, questions seemed to stump the State related to how a member of the public could determine whether the agency had done its job if the names of abortion owners, administrators, or abortionists are not public, which would thwart any search of disciplinary histories in other states.

The case began when pro-life activist Andrew Glenn made a simple request for public documents under the Maryland Public Information Act. Due to the 2011 arrest of New Jersey Steven Chase Brigham, who had been caught conducting an illegal bi-state late-term abortion scheme in Maryland, Glenn was concerned about who owned abortion clinics in his state and whether they had disciplinary history in other states.

He sought applications for abortion facility licenses, which were required under a new regulation enacted by the Maryland Department of Health in response to the Brigham scandal. These documents were public records.

Laws that protect the right of citizens to access public records are meant to ensure governmental accountability and transparency, and allows the public to serve an important watchdog function.

But what should have been a routine request resulted in a lawsuit filed by the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene against Glenn, seeking to block him –and anyone else — from obtaining information related to abortion facilities in that state.

Eric Zimmerman, an attorney with the American Center for Law and Justice who appeared on behalf of Glenn, argued that the people’s right to receive public information should not be denied based on what might happen. In fact, Zimmerman noted that the statute only provides for non-disclosure in the event that disclosure “would” result – not may or probably — in substantial injury. This places a very high burden that would tip in favor of disclosure.

Zimmerman pointed out that the current law allows for the release of the names of state licensees and their disciplinary records, and that abortion facilities should not be given an exemption especially in light of the fact that there is no correlation or causation between release of public records and violence.

This case is important because it has been through public records that the public has learned of horrific abortion abuses in Maryland and elsewhere.

“It would actually pose a danger to the public if abortion-related information was withheld from disclosure. Secrecy only deceives the public into thinking abortion is safer than it really is and denies the public critical information about abortionists that could profoundly affect a woman’s decision to abort her baby,” said Troy Newman, President of Operation Rescue. “For the government to treat abortion clinics as above the law by keeping their records secret would only result in more abortion abuses, injuries, and deaths.”

Operation Rescue is engaged in a similar public records fight in Missouri. In that case, Operation Rescue is suing the St. Louis Fire Department for denying access to public 911 records related to medical emergencies at the Planned Parenthood abortion facility in St. Louis, where nearly 30 women are known to have been transported by ambulance to hospitals due to life-threatening injuries.

Meanwhile, in Maryland, the State Supreme Court has taken the Glenn case under advisement with a decision due in the next few months.

Suit to Block Abortion-Related Public Records Requests Heard by Maryland Supreme Court